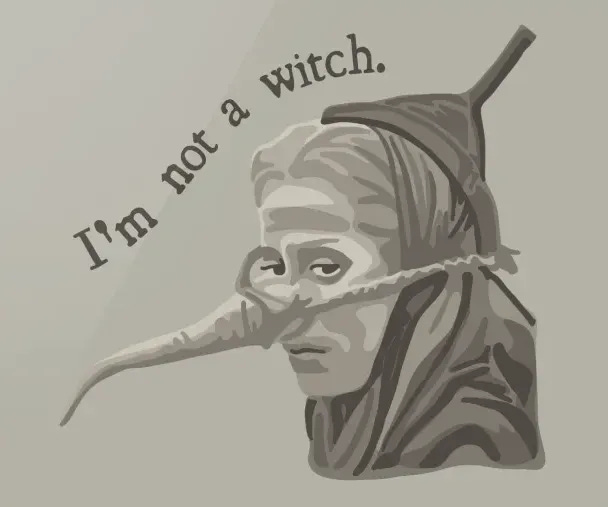

I'm not a witch.

Religious expression and spirituality in Eswatini's Christian-majority culture.

The contents and opinions of this post are mine alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Government, the Peace Corps, or the Eswatini Government.

I'm probably a witch—if you ask my host Make. At least, that's what she believed when I first moved in last November. Before putting up the curtains or tucking the sheets around my mattress, I strung a gold chain of moon phases across the windows. Instead of a tactful first impression with my host family, I locked myself in my room for a day and a half, burning local sage, playing Paris Poloma, and lighting candles instead of turning on the fully-functional lights.

Maybe I could consider her viewpoint.

On full moon nights, I also hang my moonstone necklaces around the window burglar bars. I don't know if I believe the moonlight “charges them,” but the ceremony lights something up in me. Objects become sacred when you entrust them with purpose.

I'm sure it doesn't help my No, Make, I'm not a witch case when I stay up well into the night each New Moon, playing my sound bowl and setting intentions in the darkness. These are often the nights that I stand on my sadhu board—an ancient tool for meditation, two foot-boards with copper nails poking up. I showed my Make the board. It took a little convincing, but she tried it, succumbing to my non-witchy ways.

At 11:11, I always kiss the clock and make a wish—a superstition I've held onto since my single-digit years.

Thunderstorms also hold the power to drag me outside of my house, rather than bunkering down beneath my tin roof, covering the mirrors (because they attract lightning, apparently), unplugging anything in the house (for power surges), and turning off all electronic devices (because they also tempt the lighting).

Oh! And the cards!

Of course, I have these oracle cards that I brought from the States. Apart from my yoga mat and journal, the deck's my most valuable packing list addition. Whenever I feel particularly confused and directionless, I do a reading. My first few months of service, when I was on the edge of early-terminating my contract, the cards helped me find hope and clarity in my day-to-day life. They're also sacred to me—a marker of resilience and reminder of the pathways I took to remain in Eswatini.

The cards? They are absolutely magic. But I'm still not a witch. There are magical things all around me here—the thunderstorms, the cards, the sunrises—but it's not mine.

One of the first sparks of magic I noticed flowed from the sound of toads.

My homestead is situated in the northern part of the country, where the rain and thunderstorms have been allotted frequent visiting rights. There are dams nearby, and creeks hide between the high green grasses. It's a perfect home for frogs and toads. The water is so abundant here that the amphibians have learned from it, parodying their croaks to the sound of popped bubbles and leaky faucets.

The first night I noticed the sound, I walked out of my room in the darkness, squinting into the maize fields. I had already told my Make goodnight—kuphuphe kamnandzi!—at that point. She watched me lock my door for the evening—her own ritual of ensuring my safety. So, finding me outside again, staring into the darkness, came as a surprise. But I couldn't help my awe at the new sound, like invisible bubbles were exploding all around me. It was so different than the Missouri ribbets I attribute to the frogs of my childhood.

That's when I fell in love with the toads here. Not in the Princess and the Frog way, but the otherworldly kind of love. An enraptured, wordless, floating kind of love that makes you recognize the exceptionality of the moment. Of a life. (And Make, I promise I'm not actually in love with the toads.)

Unfortunately for me and my “no witchcraft here!” argument, every Swazi woman I've ever met is fearful of them. They think they're slimy. They're gross. A bad omen. My intrigue in their water-droplet croaks quickly earned me the designation of toad-catcher at my homestead. Which I do with my hands. They do not like that.

Once, laughing with a prisoner-toad hopping between my palms, I mentioned to my sisi that a couple of these amphibians had found their way into my room.

“They're a sign of good luck and new beginnings,” I told her.

I could tell she was trying to school the appalled expression lurking behind her features. She let out a weary laugh. “Okay, sisi.” Those words like a kiss of death. Dammit. I'm sure I just sounded like a witch.

But really, I'm not.

One day, when enough details had added up to host a trial, my Make joined me on the veranda, rolling out her grass mat beside me.

Expectation feels like a held breath. Though she busied herself with a few stretches beside me, I felt the teetering anticipation of unasked questions. Finally, she tipped.

“Do you go to church, sisi?”

I looked up from my journal, doodling images of the suns, moons, and flowers. “I have before.”

Stick with the truths that will help you integrate. Don't lie and ruin trust, but weave your truths tactfully.

“So you are a Christian.” She looked relieved at the thought. It wasn't quite a question, but I knew she was digging for more.

“My mother is Catholic.” Another truth. I often attended church as a kid. In the eyes of the Catholic church, I chose them. I went as far as being Confirmed in seventh grade—though that was around the time that I stopped going altogether. I still prayed. I didn't know who—or what—exactly, I sent my words to, but if I found myself wrapped up in anxiety and loss of control, my head often tilted toward the clouds.

In usual form, I didn't stop there. I snapped the threads of woven truths and opted to overshare. “I'm not Catholic. I'm not Christian, either.” I told her that, to me, spirituality is more independent and silent. I pray on my yoga mat every day, and I keep my spirituality close to my chest.

“Who do you pray to, sisi?"

Excellent question. “I believe there is something—some higher energy that connects us all. Like a common thread between every living thing. The bugs (except earwigs, they're satan's messengers), the plants, the clouds, animals, and humans—we're part of one greater whole. The best word for what I believe in is Nature.”

She nodded, and I watched her turn over my words in her mind. Finally, Make said, “But sisi, what you speak of is Jesus. It's God.”

Treading carefully through the conversation, I pushed back on this idea. In Eswatini, Christianity filters into everything. Officially, citizens have the right to practice religion freely, and the monarchy celebrates a mix of traditional culture and Christianity (Zionism). With an estimated 90% of the population identifying as Christian, the dominant culture is apparent. Even the public schools sing gospel songs at assembly every morning. In small communities, churches are more common than convenience shops.

I don't have scripture or an established moral code to dictate what, exactly, I believe in. “But the Bible is not the book that I think explains the world and proper morals. It's often contradictory. It was written by people, not the Christian God. Not even Jesus. Specifically, it was a book written by men.”

The conversation didn't stop there. She was open to debate, thoughtful in her verse. Meanwhile, I had a greater motive in this interaction, which was to finagle my way out of weekly Church, using my yoga mat—I called it a prayer mat—as the key element in my Sunday rituals.

Luckily, the veranda conversation seemed to settle her thoughts until my sisi and niece visited that weekend, and I made a thoughtless comment about Mercury retrograde. Soon after, my Make told me about her Bible Study class and ended the conversation with, “but you don't believe in that sisi. You're into all of the supernatural stuff and magic.”

Progress lost.

Note to self: Stop talking about my Co-Star updates and classifying people's star signs.

I relented to go to church with them the following week, as to prove to them (and myself) that I wouldn't burst into flames as I crossed the threshold.

Every Sunday, I'm still asked to join them. The most difficult no's are those delivered to my six-year-old niece. She doesn't quite understand why I don't go and constantly asks, “But when are you going to hang out with us? Aren't you my friend?” I don't know if she's naturally skilled at the manipulation and heartbreak, or if the guilt trip is directed by her elders. But she's a pro.

At first, I wasn't particularly against going to church. The volunteer in me wanted to learn and experience religion through a different lens. Yes, I would go just a few times to integrate and meet people.

Prayers and celebrations look much different here from the services I attended in my youth. First, I must tell you, the music is amazing. Gospel music and dancing take up the majority of the service. Swazis get done up in their dresses and heels and bring a happy, loving, loud energy into the space that I never experienced in U.S. Catholic masses.

It's magnetic. It's beautiful. But sitting in a single-fanned (if I'm lucky) hot church, in a tiny concrete building with speakers turned ALL THE WAY UP, vibrating every cell in my body, was not how I connected to a higher power. Not to mention, I have no idea what they're saying most of the time, unless the pastor makes a point to speak in English so that I can follow along. In the first few weeks, the pastor even pulled my bhuti (host brother) up to the stage to quick-translate the sermons.

The consideration was great. Really. But all the kindness in the world couldn't keep me going.

Religion and Identity

When I applied for the Peace Corps, I signed up for an identity crisis. I volunteered to change myself, knowing that over two years of service would ultimately rewrite my assumptions about the world. I hadn't understood just how wrapped up in Christianity my service would be. It brought a new appreciation for religious freedom into my life.

I've been grappling with my religion for years now, finally finding a little bit of solace between Buddhist, Taoist, and Hindu readings. Lessons pulled from the Bhagavah Gita and the Upanishads in my yoga teacher training made more sense to me than the Lutheran and Catholic services of my childhood. For some time, I've been running down that route, feeling something in connection with nature and oneness.

Surrounded by a highly religious culture, my time to define my beliefs was streamlined so I could appropriately present myself and why I don't make weekly appearances at church. In some ways, it's helped me follow the intention I set at the beginning of the year to lean into my spirituality. I solidified a piece of my identity. In this way, Eswatini brought me closer to God, even if that god looks quite different.

Going to church had chipped away at this freshly-discovered identity, forcing myself to listen to sermons that I disagree with every school day and on the Sundays that I attend church.

That being said, the students’ gospel songs at assembly make every morning a bit brighter. There's a devotion and excitement that they bring to the school grounds that makes me love the religion. Not Christianity, but their spirituality—their love and hope. In the day-to-day conversations, I don't find myself balking, either. I see it as a piece of culture of the person that I am speaking to, reading their values, and piecing together stories of their upbringing.

It's the lecturing and doomsdays of lectures being based upon a rhetoric of “you are unworthy, but it's okay” that grates at me. Maybe I'm a little more sensitive to this due to my Catholic upbringing and overall rejection of the church. I am, undoubtedly, biased. But, to me, this sounds like the language of the colonizer that has scarred the self-esteem and self-concept of community members.

As an observer of a different culture with my own mixed history of religion, I have been looking into the roots of Christianity and its connection to colonization.

How far can we trace back this cultural shift?

Missionaries were invited to Eswatini by the Swazi King in the early 1800s. The southern region, Shiselweni, was the first area to take up the teachings of the Wesleyan Methodist Missionaries. This pre-dates colonization but would set up the groundwork for it. Colonizers would later use organized religion to give themselves the “divine right” to take over the land and establish rules under a Christian guise, offering eternal salvation as the prize for submission.

1825 was the first recorded year of missionaries in Eswatini (then Swaziland). This idea was first introduced by King Sobhuza I. As the story goes, just before his death, the King had a vision of white people coming into Swaziland with umculu and indilinga—the book (Bible) and money. Following the vision, he warned that the people of Eswatini should follow the umculu and not be steered by money. His predecessor, King Mswati II (1820-1868), formally invited the missionaries to bring the “word” to his people. In 1844, the first Christian church was established in Mahamba, near the southwestern border.

Supported by the dual monarchy, Christianity spread throughout the country over time. Christian organizations and missionaries built schools and clinics, entwining their charitable contributions with the word of God, celebrating the rise of literacy in biblical teachings.

Eventually, white settlers grew in numbers and, in 1877, the British would annex Swaziland, a landlocked nation within South Africa. Independence and colonization came in phases, changes lasting for a decade or two in various power struggles. It wouldn't be until 6 September 1968 that Swaziland would declare the independence it experiences today. By this time, the religion of the colonizers was firmly rooted in the land.

Swazi monarchies have aligned with Chrisitianty since it was first introduced, mixing traditional values with the church, though the country exercises freedom of thought, religion, and assembly, which was signed into the national constitution in July 2005 by King Mswati III. Officially, Swazis have freedom of worship as long as it is registered with the government, though the royal events host Christian ideology.

Christianity has been woven into the school systems and Swazi life for decades, though compulsory Christian education occurred recently. In 2017, the government of Swaziland, renamed to Eswatini in the following year, mandated Christian education in all public schools, primary and secondary. Upon its decree, this mandate received pushback from minority religious groups, as there is no “opt-out” option for students of differing spiritual practices, and national exams would include Christian education.

Christianity in Schools

Throughout my time in Eswatini, I have taught in a Mission school and a public school. From what I experienced, the emphasis on religion largely altered the attitudes and practices within each school. The argument for corporal punishment was much more common and aggressive at the Mission. "Spare the rod, spoil the child” (Proverbs 13:34) was an excuse I heard every time I sought to enforce positive discipline tactics. In addition, every week, a preacher would visit and give hours-long sermons. The other days, teachers would take the lead in long prayers and religious lectures.

All the Mission-school teachers I worked with were expected to participate and lead morning prayer. These sermons, focused on sin and sacrifice, were meant as lessons for the student body and staff. The head teacher often commented on other teachers’ church attendance and out-of-work activities. He once said that he was assigned his position to carry the word of God and guide the school community to follow to Bible and walk in the footsteps of the Mission's founder. The reality is, the hierarchy and assumed “divine right” of the headteacher correlated with tactics of the colonizer.

The rhetoric of student unworthiness and the call for constant repentance slows the curve of human rights and affects the community's mentality toward social and health topics—birth, abortion, sex education, women's rights, and HIV prevention. As a Life Skills Education teacher, I felt like the attitude tainted students' self-concept more than anything. How do we boost the self-esteem and motivation of a student body that is taught to think that something is inherently wrong with them?

That's what they were told, repeatedly, every morning.

How do students question morality or even educational materials when the attitude toward questioning higher-ups is seen as questioning the word of God? To me, morning assemblies at the Mission school sounded like the battle hymns of the invaders, recorded into scripture and retained post-independence.

Ancestral Guilt

As a white person going into the community as a volunteer, I had, and often still have, an ancestral guilt tied to the actions of the English settlers. It was hard to go into the school every day and realize that the very things I was trying to teach—the use of positive discipline, HIV prevention, sex education—were largely due to the scars left by colonizers who looked like me. Light skin, blonde hair, light eyes.

I wondered if, when students look at me, they were thinking of the people they learned about in their history classes.

And yet, possibly due to the lasting positive reputation of the missionary who established the school I worked at—the missionary who still has his photograph hanging in the church beside the image of the king, queen, and a white Jesus—my work was seen as saintly and highly esteemed.

This caused an identity crisis that went beyond my spirituality. I felt it crawling all over my skin, tangled in my hair, flecked in my eyes.

When I first met my community counterpart, he called me a missionary. I nearly choked, quickly correcting him.“No! No, I'm not a missionary,” I told him. "I’m a witch.”

Just kidding! I swear, Make.

Comparing this experience to teaching at the public school, in a more progressive part of the country, some teachers were outwardly non-religious and allowed to step back from leading prayer. For me, this change greatly affected my mental health. Morning speeches were filled with fewer threats of God's wrath, but a hope of fulfilling students’ goals and prayers for support in the journey. The sticks of discipline still landed, but much less often. Punishment was reactive rather than proactive to keep students “on the path of God”.

I didn't dread the mornings like I had previously. I stopped crying after assembly, wiping my face behind locked doors. I went from strictly hiding who I was—my tattoos, my legs in ankle-length skirts, my social habits, and my spirituality—to feeling safe to speak about being a non-church-attending-sage-burner. The teachers, leadership, and students were more curious than judgmental. In the conversations I had with students and teachers about religion, it seemed to give them more affirmation of their own beliefs. The questioning led to critical thinking, and their attachment to the Bible was based on their own loving devotion rather than a fear of non-conformity.

In a more modern space, where the ability to speak of my beliefs, cast out ideas, and shake up the norm, I've finally regained some of the lung capacity that felt stifled in my previous community.

There are still pieces of myself that I hide, of course. Some elements of Me, I shed completely. Others have simply evolved as I've integrated into this new culture. In the past 10+ months, I've gone through piles of tear-stained tissues, stacks of historical commentary, and unforgettable experiences.

What sticks out the most are these revelations of what it means to change within a culture and what it feels like to have a culture change you. But I had a choice in all of this. I've had a choice to explore my religion, read other texts, and miss religious gatherings. I've aged enough in a culture where Christianity wasn't my sole option, and the strict environment where I had that freedom limited only lasted for two months. I was at a Mission school for two months before the structure got to me. And I had the option to leave. How would it change my mentality to grow up in a space where this decision was made for me? A space where what I was being taught was intuitively unaligned with my values and beliefs? How long would I last before I would need to speak out against the structure or submit to the hierarchy?

Lately, I've found myself holding on tighter to the spirituality and rituals that feel like connection—the ceremonies that feel like oneness. In the new space of expanded freedom and safety of conscience, I've felt this urge to question everything, loudly—to rethink all the propaganda laced in history, curated by the victors.

And historically, the women who do that? They called them witches.

Make, maybe you're onto something.

Hey, lovely! I would love to hear what you think. Which experiences have made you shrink? Which have made you grow? How did you stumble upon your spirituality, and what pulls you along that path you're on now?

LINKS & FURTHER READING

Learn more about religion, Swazi history, colonialism, and regaining independence.

Influence of Christianity in Eswatini, Afro Discovery (2024)

The Freedom of Thought Report, Eswatini, Humanists International (2022)

Swaziland renamed to Eswatini by decree of the King, The Guardian (2018)

Report on International Religious Freedom: Swaziland. U.S. State Department (2017)

The Swazi dual-monarchy, the religio-cultural genius, H. Ndlovu (2007)

This piece is beautiful ‼️ So much to consider, written thoughtfully & with humor🙂 I too loved the morning song— corporal punishment— not so much😢